The conditions for this to happen, however, are still not in place in Germany.

The asphalt is still piping hot when Mike drives his steamroller over the surface of the new road one last time. There is a strong smell of bitumen in the air – that viscous mixture of hydrocarbons that is obtained from petroleum and moulds the small grains of stone in the tar into a smooth, uniform carpet, over which heavy lorries will transport their goods, people will commute to work and bikers will welcome the sun’s first rays in spring over the coming years.

Mike is a road worker at one of the many road construction firms somewhere in Germany and, like so many in his industry, he only uses virgin aggregate to complete his projects.

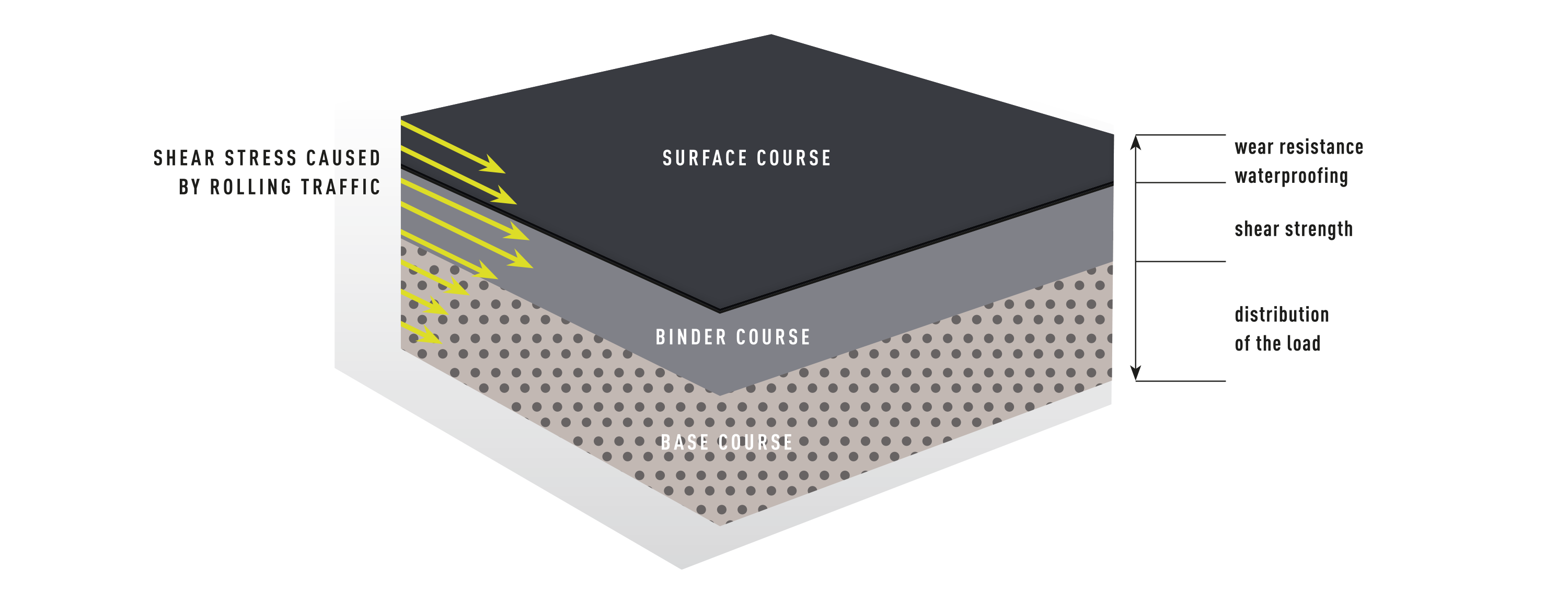

Mike has driven over the same stretch of road too many times to count. Every single layer has to be compacted so that the road will be able to withstand not only the enormous pressure exerted by the traffic but also the effects of the weather. The only thing that the drivers can see when they are in their cars is the top layer, the so-called surface course.

A road really is a high-tech construction that consists of a number of different layers or courses – sometimes more, sometimes fewer depending on what the road will have to withstand. The surface course is the asphalt, the binder courses below it even out any surface irregularities and the base courses have to be able to withstand a great deal – as the huge loads caused by the traffic are passed down to them. Which is why Mike has to really pack down and compress the materials with his steamroller or the road surface will be damaged in no time at all. And that means more annoying roadworks. For the most part, there is also a frost protection layer at the very bottom of the road. Its job is to make sure that any water flows away quickly so that the road is not damaged by frost.

Many public authorities putting projects out to tender still want virgin raw materials to be used in their roads. These materials, however, are becoming ever scarcer, in Germany as well. A variety of aggregate can be deployed to build the base and sub-base courses. Mike’s employer only uses sand and gravel, as do the majority of the firms operating in the sector. This is what many public authorities want – be it implicitly or explicitly – even though there are other good alternatives and the German Circular Economy Law [KrWG] now stipulates that these alternatives should be used.

How roads are designed

Source: https://www.asphalt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/technik/asphaltschichten_und_ihr_aufgaben.pdf

Paper is patient and companies like Mike’s employer need new projects. And yet virgin aggregate like sand and gravel are finite. And it is getting more and more difficult to get hold of them.

It is not because there is a lack of deposits. “The way Germany was formed means that there is an almost infinite amount of sand in the ground,” Harald Elsner from the BGR [Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources] noted a few years back in a short study about aggregate raw material supplies. Too many areas of Germany have been built on, too many areas have been planned for and it is too densely populated to be able to get at all this sand.

According to the BGR, for example, 85% of the surface area of the German state of Baden-Württemberg has already been planned for other uses. Protected waterways, nature reserves, areas of outstanding natural beauty and developed land all prevent the sand and gravel from being extracted.

A resource-friendly alternative would be to use the ash from waste-to-energy plants – simply referred to as IBA by those working in the industry. It has, though, been very difficult to market IBA as a substitute aggregate in Germany for many years now.

Over six million tonnes of minerals cleaned by the fire

Not all wastes can be recycled for reuse. Residual household waste, for example, is thermally treated by the almost 70 waste-to-energy (WtE) plants in Ger-many and used to generate, for the most part, heat and electricity.

These WtE plants incinerated around 13 million tonnes of so-called mixed municipal waste (primarily household and bulky waste from local residents) in 2019. In addition to this, they also treated commercial waste. It is not possible to put an exact figure on these volumes but it must be about the same amount as the municipal waste.

Many construction firms also have waste materials that cannot be recycled and must be incinerated – old wood, for example, that has been treated with chemicals. With the fire reaching temperatures of over 800°C, these pollutants are safely destroyed and can no longer harm either humans or the environment. These mixtures of waste often contain mineral fractions that simply fall through the furnace grate.

Around 25% to 30% of the waste (by weight) handled by a normal WtE plant is mineral material. Some are calling it a scandal to simply dispose of these minerals, especially as the country has put the circular economy and resource conservation at the top of its agenda. According to the latest figures published by Destatis [Federal Statistical Office of Germany], over six million tonnes of this material were generated in Germany in 2019. One-fifth was sent straight to landfill – a total of 1.3 million tonnes. In reality, this figure was much bigger but the material was first processed in so-called IBA-processing facilities – almost 4.7 million tonnes in all.

IBA processors’ primary focus is on the metals

The majority of processing plants are only really interested in the ferrous and non-ferrous metals in the IBA. These can be sold on to industrial businesses and are a good source of income.

According to a study compiled by Kerstin Kuchta, a scientist at the University of Hamburg, around 10% of the IBA’s content is made up of metals. Around 80% of this is iron and can be removed from the rest of the IBA comparatively easily by using a magnetic separator. Getting to the high-priced non-ferrous metals is considerably more difficult.

But where there’s a will, there’s normally a way: thanks to state-of-the-art systems, IBA processors are now able to recover even the smallest particles of copper and aluminium as well as gold, silver, platinum and palladium from the ash.

However, 90% of the IBA is made up of minerals – and far less effort is spent on this material. This mineral fraction is washed, sorted according to type and stored for several months. This storage period – so-called ageing or weathering – stabilises the material as a number of chemical processes take place and the heavy metals become more closely bound. This makes it more difficult for them to be washed out so that the risk to the environment is negligible.

Having been processed, the IBA has comparable structural properties to the sand and gravel used by road workers like Mike to build the base and subbase courses. Mike could, therefore, easily use this substitute aggregate, conserve natural resources, cut costs.

Landfill construction claims to be part of the circular economy

As mentioned above, though, firms like Mike’s employer do this far too seldom. Instead, the majority of the IBA ends up at landfills as material for construction work. Using IBA in landfill construction measures has been classified by the UBA [Federal Environment Agency] as a “low-ranking recycling measure”.

Officially, therefore, the IBA is being recycled; in practice, though, it is not really contributing towards the circular economy.

The German aggregate sector could also be one of the reasons for this: in 2018, a request submitted by Bettina Hoffmann from the Green Party (then a German MP and now a parliamentary undersecretary at the Ministry for the Environment) to the Government revealed that around 3,900 stone and clay quarries and gravel and sand pits and 30 mines supply German road construction projects with virgin aggregate. With 294 administrative districts and 107 independent city councils in Germany, that is an average ten pits or quarries per local authority – all of them sources of business tax that no councillor is voluntarily going to give up.

The mining and quarrying of aggregate is big business with the construction sector booming in Germany: Miro [German Mineral Products Association] estimates that around half a billion tonnes of aggregate are mined in Germany every year. According to the BBS [German Association for Building Materials – Stone and Earth], approx. 2.3 billion tonnes of aggregate were used between 2010 and 2016 (not including the production of concrete) – an average 330 million tonnes per year.

And so, rather than being used to build public roads, the IBA ends up – either directly or indirectly – at landfills, further aggravating the already strained landfill capacities. According to a study published by Prognos in 2020, Germany will have no free landfill capacities left by 2033 at the latest. A situation that will again benefit quarry operators: it is not rare to see gravel and clay quarries being given a second life as a construction waste landfill site once all the raw materials have been extracted.

in 1,000t / Source: Destatis

The Netherlands are showing how things could be different

This waste of resources in Germany has the same structural causes as can be found in the resource-rich developing countries that extract their mineral resources unchecked. The Netherlands have been showing for years now that things can be done differently.

Our neighbours do not have as many deposits of virgin aggregate as we do. They rely on imports. Operators of gravel pits and stone quarries in Germany alone exported almost 20 million tonnes of aggregate to the Netherlands between 2010 and 2017.

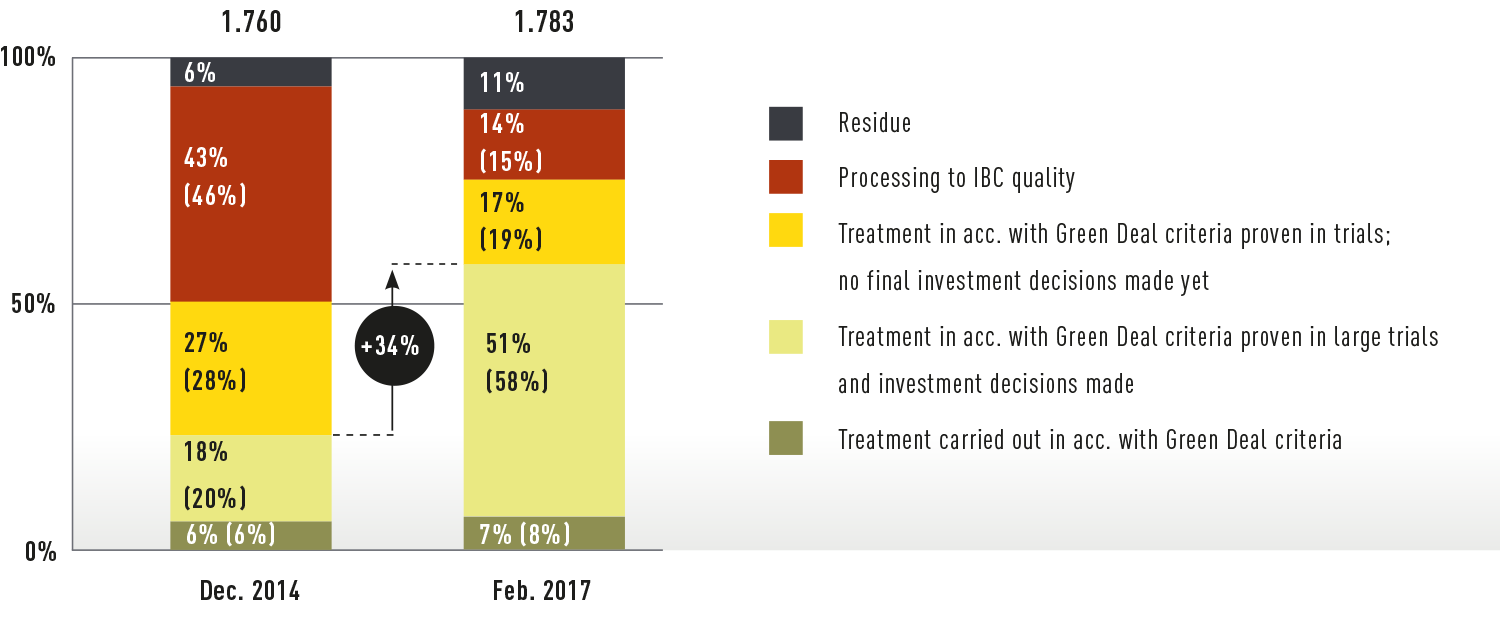

Importing aggregate, however, makes a country dependent on others. Those that want to be independent must come up with innovative recycling solutions. The Dutch government has known this for a long while and negotiated a so-called Green Deal with its waste management sector around ten years ago. Put simply, they agreed that the material could be used in more projects if the IBA processing systems were improved.

The goal was to be able to freely use IBA from WtE plants as aggregate without any further “isolatie-, beheers- en controlemaatregelen” (IBC), i.e. insulation, management and control measures. And so the Dutch waste management businesses invested in IBA processing facilities, for example to further reduce the heavy metal content.

Thanks to the introduction of the Green Deal, these new systems have improved the quality of the processed IBA in the Netherlands to such an extent that it has been able to be used as normal aggregate in road construction projects with absolutely no restrictions since the beginning of 2022. IBA may no longer be used in IBC measures; it has been forbidden for a while now to send it to landfill or export it.

Advances made in IBA processing in the Netherlands; 2020 Target (100%)

Source: Jan Peter Born, HVC 2017

Thanks to the introduction of the Green Deal, the new systems have improved the quality of the processed IBA in the Netherlands to such an extent that it has been able to be used as normal aggregate in road construction projects with absolutely no restrictions since the beginning of 2022.

The Umbrella Ordinance: a controversial solution for Germany

The so-called ‘Mantelverordnung’ [Umbrella Ordinance on Substitute Building Materials/Soil Protection] aims to improve the use of substitute aggregate in civil engineering projects in Germany. When Florian Pronold, the former undersecretary at the Ministry for the Environment, spoke about the Umbrella Ordinance in the Bundesrat (Germany’s upper house) last summer just before the members voted, he compared it to Michael Ende’s novel “The Neverending Story”. Central government, the German states, the construction sector, waste management firms, local authorities and anyone else in Germany who had any-thing to do with aggregate had argued about the ordinance for 16 years. As a result, this set of rules is now complicated and contains many compromises that, the circular economy believes, are inadequate in many cases. Having said that, this solution is probably better than having nothing at all. The Substitute Building Materials Ordinance, which is regulated by the Umbrella Ordinance, defines three categories of incinerator bottom ash aggregate (IBAA) called HMVA-1, HMVA-2 and HMVA-3. The Umbrella Ordinance sets out material qualities for each individual category and specifies what they may be used for.

However, even the highest quality of IBAA (HMVA-1) with the strictest material values is regarded as waste – a psychological black mark that virgin aggregates do not have even though their pollutant and heavy metal contents are, objectively, higher than those in the IBAA. Under these circumstances, it is unlikely that Mike will use more incinerator bottom ash from WtE plants to build the load-bearing courses under German roads in the future.

The future: high-tech processing for building construction work

While the highest recycling goal for IBAA in Germany is road construction work, the Netherlands have already gone a step further. REMONDIS’ subsidiary Heros operates one of the largest IBA processing facilities in Europe. Situated in Sluiskil on the Ghent-Terneuzen Canal between the two major ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp, this 45-hectare site processes up to 700,000 tonnes of IBA from the Netherlands and Belgium every year. This is equivalent to the amount of household waste generated by around six million local residents.

Heros’ specialists have developed a ‘hydro-mechanical washing’ system that enables them to produce a particularly high quality of aggregate with a particle size of 0-14 millimetres. During this two-stage process, the mineral materials are repeatedly washed and screened until they have generated a cleaned aggregate that is effectively free of pollutants and heavy metals.

It is not only possible to use Heros’ aggregate for road courses but also to produce asphalt and concrete – which means it can be used to construct buildings. By the way, this washing process also enables copper, zinc, lead, high-grade steel, gold and silver to be recovered which metalprocessing businesses are happy to buy from them.

The line between virgin and secondary aggregate is, therefore, becoming increasingly blurred in the Netherlands. Spurred on by its lack of natural resources, the country has become inventive. Germany could also substitute some of its demand for virgin raw materials with recycled material, including the IBA from WtE plants.

The technology is there. What is lacking is the political will. It makes no difference, quality-wise, whether Mike drives his steamroller over sand and gravel or over synthetic aggregate like the material produced by Heros: Dutch roads are certainly not known for being worse than those in Germany.

Image credits: image 1: Adobe Stock: Volodymyr Shevchuk; images 2, 3: Adobe Stock: Artem Zakharov