It is cold inside the Alpine centre in Bottrop – a town in the heart of Germany’s Ruhr region – with the temperature inside the building having to be kept at a permanent 5°C. Warm clothes are a must all year round even if the temperatures outside mean the outdoor swimming pools are full of visitors. This indoor skiing venue opened its doors to the public in 2001 and boasts a 640-metre ski slope (with a 77-metre difference in height from top to bottom) – making it the longest indoor ski slope in the world. A genuine highlight in a region that is still going through a structural change.

And yet this dream of being able to ski in the middle of this industrial region almost came to an abrupt end just ten years after the centre opened: in 2011, structural engineers discovered that some of the pillars supporting the snow centre had shifted. The area had to be filled with 450,000m³ of material to stabilise the building. Which meant that a material needed to be found that not only met the technical requirements but was also available in sufficient quantities.

“We worked together with MAV in Krefeld to develop a concept that met all the building requirements and was economically viable and environmentally safe as well,” explained Berthold Heuser, an authorised signatory at REMONDIS’ subsidiary REMEX. A combination of the recycled aggregate GRANOVA (quality-assured, processed incinerator bottom ash (IBA) from household waste-to-energy plants) and iron silicate sand from AURUBIS’ copper recycling business met all the technical requirements regarding stability, permeability and weight.

The stabilisation of the snow centre in Bottrop is a flagship project promoting the circular economy in the construction sector: it is regional, it is sustainable and it is resource-friendly. The way the world should be. “Every year, our group returns more than four million tonnes of recycled aggregate to market at home and abroad,” Heuser continued. This helps conserve landfill capacity and natural resources in equal measure. And yet, this is still not enough.

Not having an end-of-waste regulation is making it difficult to market recycled aggregate

The right statutory framework must be in place, however, if more recycled aggregate is to be used in meaningful projects like the one at the Bottrop ski centre. One problem is that recycled aggregate continues to be classified as a waste product. Even though it meets very strict quality standards and even though it may, by law, be used in clearly defined construction measures. Its status as a waste product makes it more difficult to market: on the one hand, for purely psychological reasons, as some market players still worry that using recycled aggregate will be creating a problem for the future – a fear that is completely baseless. And on the other, for legal reasons, as many companies that use aggregate are not permitted to accept waste. Instead, they must work with virgin raw materials even though there are recycled materials available on the market that meet all the building requirements and are just as good for the application in question.

Despite the positive examples like the snowdome in the Ruhr region, the picture is not so rosy when you look at the overall figures. Less than 800,000 tonnes of the approx. six million tonnes of IBA produced in Germany in 2020 were used to construct ‘technical structures’ – i.e. structures such as roads and the ski centre in Bottrop. That means that the recycling rate lies at a mere 13%. 3.9 million tonnes ended up, more or less unused, at landfills instead.

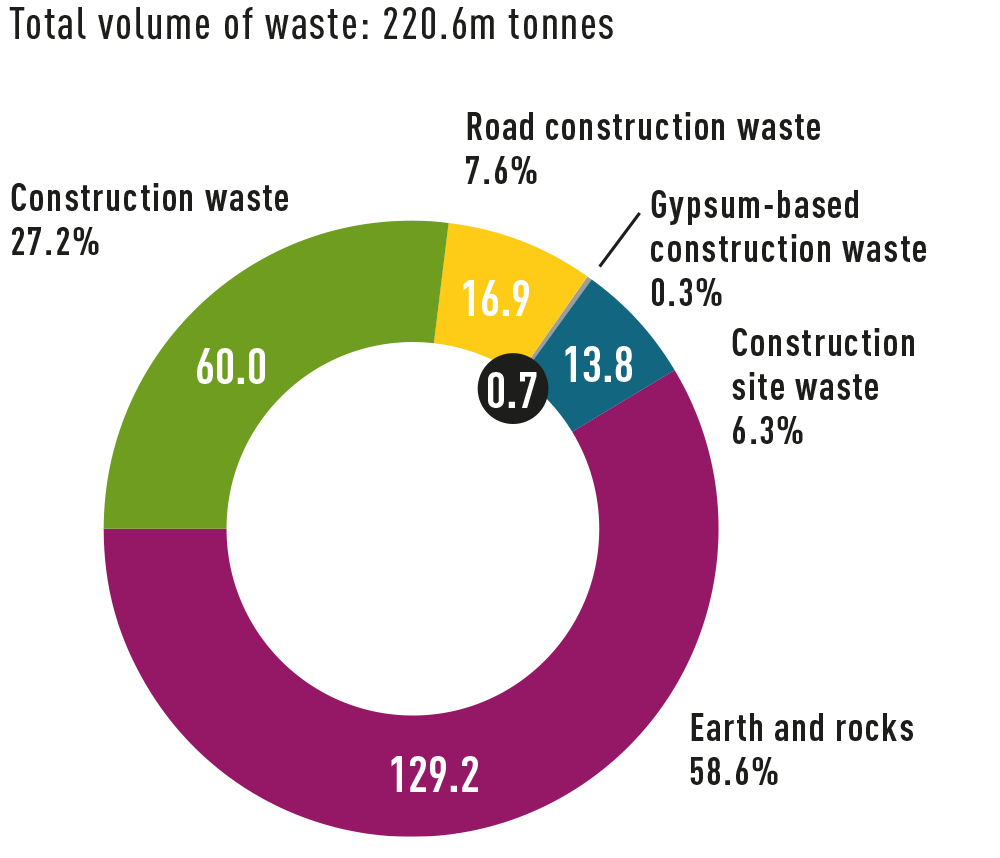

Recycled aggregate produced from mineral construction waste also suffers from the fact that it is still classified as waste rather than as a product. Figures published by Kreislaufwirtschaft Bau (an alliance of construction and circular economy associations) show that around 220 million tonnes of mineral construction waste were generated in Germany in 2020. Which means that every second tonne of waste produced in Germany was construction and demolition waste. According to the UBA [Federal Environment Agency], this means that mineral construction waste will play a key role in creating a closed circular economy.

A great deal still needs to be done, however, if it is to live up to this key role. Take a closer look at the numbers and the picture is more nuanced as the recycling rates differ greatly between the various material streams. Around 80% of construction waste (which, lying at 60 million tonnes, makes up just over a quarter of all the mineral waste generated) is recycled. This is a good amount. In contrast, just 10% of earth and rocks (the largest fraction at almost 130 million tonnes) is processed into recycled aggregate. It may be true that the majority of this huge material stream is used. In this particular case, though, ‘used’ also means utilising it as a building material in landfills or surface excavations and not necessarily in technical structures such as roads.

Those responsible for planning Germany’s Mantelverordnung or ‘Umbrella Ordinance’ (a large environmental policy project, of which the EBV, i.e. the Substitute Building Materials Ordinance, was the most controversial) estimated a few years back that there would be around 38 million tonnes of recycled aggregate every year. A figure that was far too low looking at the current demand for this construction material and the amount of mineral waste actually being processed. According to Kreislaufwirtschaft Bau, 77 million tonnes of recycled aggregate were produced from construction waste, road construction waste, and earth and rocks in 2020. And even more is possible – if the conditions are right.

Statistically recorded volumes of mineral construction waste in 2020 (in million t)

Kreislaufwirtschaft Bau: Mineral construction waste monitoring in 2020. A report on the generation and use of construction waste in 2020, Berlin 2023, available online in German at: https://kreislaufwirtschaft-bau.de/Download/Bericht-13.pdf (06.01.2024)

The EBV aims to create uniform solutions for the whole of the country

“As far as technology is concerned, there are no obstacles whatsoever to processing large quantities of mineral waste so that it can be used sensibly as recycled aggregate,” commented Heuser. “We’ve been doing this in the Netherlands for many years now.” REMEX’s subsidiary HEROS Sluiskil B. V., for example, processes IBA at its HEROS Ecopark Terneuzen, a site covering 45 hectares. It is able to produce a material of such high quality that it can be used to make concrete for building products. HEROS does this by deploying a complex system that not only removes the heavy metals from the mineral substances but also improves their environmental properties.

Germany’s federal system had a negative impact on the processing and recycling of mineral fractions for decades. Until just recently, each German state had its own rules and regulations about where and under what conditions recycled aggregate may be used in building projects. While efforts were made by the German states to create uniform conditions via LAGA (the federal states’ working group on waste), the lowest common denominator was the very best that they ever managed to achieve. Germany did not have a nationwide market for substitute building materials – something that would have led to economies of scale for recyclers and made the recycling of such materials more cost-effective.

The goal of Germany’s Substitute Building Materials Ordinance – referred to simply as the EBV – was meant to change all this. After 16 endless years of holding negotiations and searching for compromises, it finally came into force last August. There are two main objectives behind this ordinance: to define the criteria and permitted limit values for the different types of substitute building materials and to determine the rules about how these materials may be used in building projects. Limit values and permitted areas of use are two sides of the same coin as they ensure that recycled aggregate and other substitute materials are put to the very best use and protect soil and waterways from becoming contaminated. By definition, therefore, a building material that has been produced in accordance with the EBV and is used in line with the criteria set out in this ordinance poses no risk to humans or the environment. That’s the idea. Valid across the whole of Germany, this ordinance could create the market conditions needed for these mineral materials to play a key role in creating a closed circular economy.

Could. It would appear that the politicians do not fully trust their own ordinance. During their discussions about the EBV, central government and the German states were unable to bring themselves to automatically declare substitute building materials that are produced and used in accordance with the ordinance as ‘products’. Which is why these building materials continue to be classified as waste despite the new Substitute Building Materials Ordinance. The German government now wishes to set out end-of-waste rules in a separate ordinance, the ‘Abfallende-Verordnung’ [End-of-waste Ordinance]. According to the so-called key issues paper presented by the Federal Ministry for the Environment at the end of last year regarding the End-of-waste Ordinance, just a selection of substitute mineral building materials from the highest material category will be able to shed their status as waste and be called a product instead. The reason given by the Ministry for this is the possible impact they may have on humans and the environment even though the concept for the EBV – drawn up by specialists over many, many years – ensures that such recycled materials are safe.

Figures published by Kreislaufwirtschaft Bau (an alliance of construction and circular economy associations) show that around 220 million tonnes of mineral construction waste were generated in Germany in 2020.

Restrictive end-of-waste ordinance is thwarting circular building

An end-of-waste ordinance that is too restrictive, however, could make the framework conditions for substitute building materials worse rather than better. It would simply reinforce the tendency that is already there on the market today to only use the highest material categories (such as RC-1). “It would, totally unnecessarily, devalue many types of recycled aggregate,” said Heuser criticising the Federal Environment Ministry’s plans.

On top of this, there is the issue that not all mineral waste can be recycled into substitute building materials. Material that is contaminated with asbestos or other dangerous substances may not be returned to market but must be deposited safely in landfills instead. REMEX fears that the EBV and end-of-waste ordinance might result in mineral fractions, which are being recycled into substitute building materials at the moment, being sent to landfill in the future. Landfill space, which is already scarce in Germany, would then be filled with materials that could be used, without hesitation, to construct roads if the framework conditions were more favourable.

REMEX proposes an easy-to-understand, end-of-waste regulation

As a result, REMEX has put forward a proposal for an end-of-waste regulation for substitute building materials that is easy for everyone to understand. Namely, that all substitute building materials and material categories should be given product status if the materials are used in line with the EBV. “The EBV’s new regulations created a long overdue, scientifically based, nationwide framework,” explained REMEX managing director Michael Stoll. Despite this though, each German state continues to do their own thing as there are no national end-of-waste regulations. “At the moment, a patchwork of new – sometimes contradictory – rules is being set up, creating yet more red tape,” Stoll continued.

If natural resources are to be conserved, climate change tackled and biodiversity protected, then there is no getting around the fact that there must be more recycling. The circular economy will not, however, be able to cover the demand for raw materials by itself. 585 million tonnes of aggregate were produced in 2020 and just 220 million tonnes of mineral waste generated during the same period.

Which is why Berthold Heuser does not see recycled aggregate as a rival product for companies producing aggregate from virgin materials. “What we need is a healthy mix of recycled and virgin building materials,” he concluded. Virgin building materials could then be used more in high quality applications, for which there are no recycled substitutes at the moment.

It is just after four in the afternoon at the Bottrop snow centre and it has got a little louder as a group of children get off the lift laughing: the Kids Club has stepped onto the slope. This venue makes it possible for children aged seven or older to ski regularly without having to go on an expensive skiing holiday. Close to where they live, in the heart of the Ruhr region. The children are almost certainly not aware of the fact that it is thanks to recycled aggregate that they have a safe place to enjoy this winter sport. And would probably not be very interested either if they did know.

“What we need is a healthy mix of recycled and virgin building materials.”

Berthold Heuser, Authorised Signatory at REMEX

Image credits: © REMEX