When Carsten Ketteler talks about gypsum you could listen to him for hours. Where gypsum is found. All the things you can do with it. All the places it is needed. Ketteler is managing director of REMONDIS’ subsidiary CASEA and obviously enjoys what he does. CASEA produces and sells high quality products made of calcium sulphate, i.e. of gypsum. “Annual demand for gypsum in Germany lies at around ten million tonnes,” Ketteler said. In contrast, just 700,000 tonnes of waste gypsum are generated each year. Ketteler explained that the big difference between the two can be put down to the big drywall boom that began in the 80s – a time that saw construction firms starting to install large volumes of plasterboard. “The buildings that are currently being demolished don’t necessarily contain large amounts of recyclable

gypsum-based waste.”

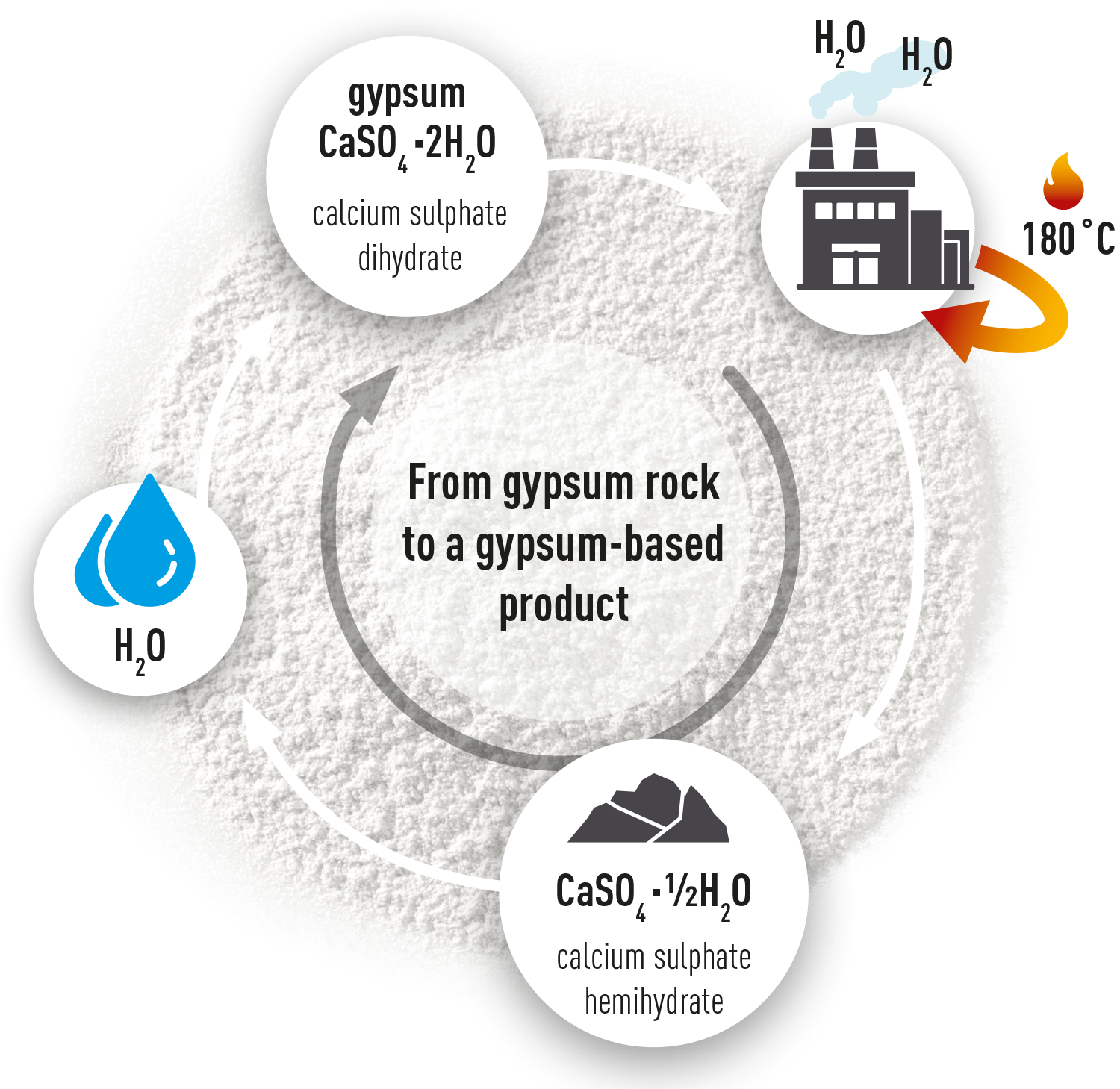

Gypsum-based construction waste is not normally listed in waste statistics as it only makes up a mere 0.3% of all mineral waste generated – as can be seen in the latest figures published by Kreislaufwirtschaft Bau (a circular economy construction initiative). Having said that, gypsum is an excellent material for promoting circular building as it can, just like glass and metal, be recycled an infinite number of times without losing its quality. The principle behind recycling gypsum is really very simple: the gypsum rock is gently fired at a temperature of 180°C allowing the water contained in the input material to escape.

Water is then added again to the intermediate product – calcium sulphate hemihydrate. This process creates calcium sulphate dihydrate, the chemical term for gypsum. Water out, water in: recycling gypsum is not rocket science. But, as is always the case with recycling, it is all about the purity levels of the input material.

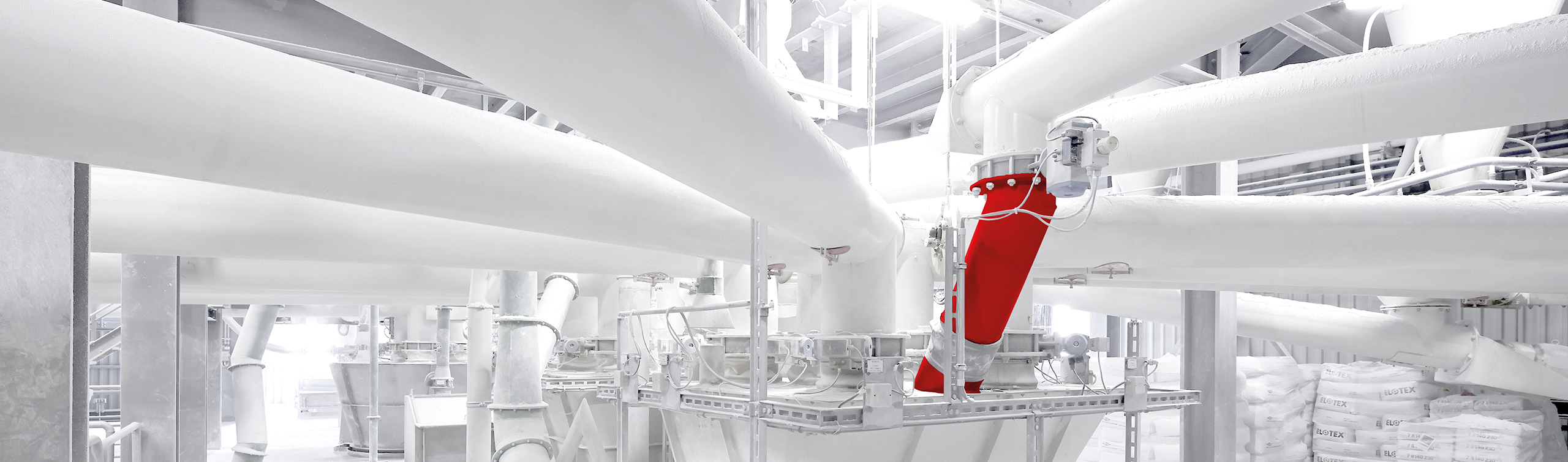

There are four gypsum recycling plants in Germany. One of them is located in Zweibrücken, a town in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, and has been operated by REMONDIS since 2018. The company also owns a 50% share in the MUEG facility in Großpösna. The system used by the facility in Zweibrücken sees the gypsum-based waste first being pre-sorted. The material then undergoes several processing and shredding stages so that the output is of a high quality. The recycled gypsum can be reused straight away as it meets the specifications needed by companies producing gypsum-based plaster products. This recycling plant, however, operates well below its potential capacity. Each year, it could produce up to 72,000 tonnes of pure gypsum for industry. This figure is, however, much lower at the moment.

“Annual demand for gypsum in Germany lies at around ten million tonnes.”

Carsten Ketteler, Managing Director of CASEA

Over half of all gypsum-based waste is landfilled or used as backfill

Instead of sending gypsum-based construction waste for high quality recycling, large volumes are still being landfilled or deposited in mines. According to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis), around 300,000 tonnes of gypsum-based waste listed under the waste code 17 08 02 were sent to landfill in 2020. A further 106,000 tonnes ended up in open-cast mines, a lower quality form of recycling.

Figures published by Kreislaufwirtschaft Bau show that a total of ca. 700,000 tonnes of gypsum waste were generated in Germany in 2020. According to Destatis, therefore, over 400,000 tonnes of this gypsum-based waste (i.e. more than half) were not recycled but landfilled or deposited elsewhere. In its latest status report, Kreislaufwirtschaft Bau states that around 442,000 tonnes of gypsum-based waste were sent for processing in 2020. This figure does not, however, reveal how much is actually recycled for reuse.

According to the German Mineral Resources Agency (DERA), a mere fraction of the gypsum-based waste generated was recycled for reuse in 2020, namely 63,000 tonnes. Scientists assume, however, that approximately half of the gypsum-based waste produced in Germany could be recycled for reuse.

Depositing gypsum-based waste in landfills regularly causes problems as gypsum can sometimes dissolve in water. If water gets into the main body of the landfill, then it can wash out the gypsum, resulting in it accumulating in the leachate system. One of the main reasons why gypsum-based waste continues to be sent to landfill despite this problem is because there are such small volumes. “Renovation work generates small amounts of plasterboard compared to the other types of mineral waste. Unfortunately, they tend to be taken to landfill rather than one of the four recycling facilities because of the costs involved,” explained Ketteler. Some of the old plasterboard is even transported to the Czech Republic where it is used to clean up uranium slurry ponds. And then there is the gypsum-based plaster that is stuck to the tiles when a house is demolished. “No one’s going to scrape it off and transport it, possibly hundreds of kilometres, to one of the four recycling facilities.”

Since the new landfill ordinance came into force at the beginning of January, it has been forbidden to send recyclable waste to landfill. Things are unlikely to change, however, when it comes to gypsum as it is questionable whether more material will be recycled for reuse as long as backfilling is categorised as a form of treatment. And yet the capacities that have been set up across Germany to recycle gypsum are certainly not being fully exploited. Figures published in the study that the ecological institute, Prognos, and the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (BAM) carried out for the German Environment Agency (UBA) show that Germany could realistically be generating up to 800,000 tonnes of recyclable gypsum-based waste in 2030.

Water out, water in: the principle behind recycling gypsum is really very simple – what’s challenging is the logistics

Source: Federal Association of the Gypsum Industry: The CaSO4 & H2O system, available online in German at: https://www.gips.de/wissen/rohstoffe/das-system-caso4-h2o (24.01.2024)

Phasing out coal will lead to a scarcity of gypsum

The careless way people are handling this recyclable gypsum is all the more astounding in the face of a worsening gypsum crisis. Almost half of today’s demand for gypsum is covered by so-called FGD gypsum – i.e. gypsum from the flue gas cleaning systems operated by coal-fired power stations. The flue gas desulphurisation process produces a calcium sulphate compound as a by-product. From a chemical point of view, this substance is identical to natural gypsum and has the same structural properties. This FGD gypsum is, therefore, used to make building materials just like natural gypsum. FGD gypsum is produced when liquid lime is injected into the flue gas to bind the sulphur dioxide. Air is then added so that the oxidation process produces gypsum.

Just like natural gypsum, FGD gypsum is used to make building materials such as plaster, plasterboard and screed. Gypsum is also of use to other sectors – for example, food production, the fertiliser industry and dentistry.

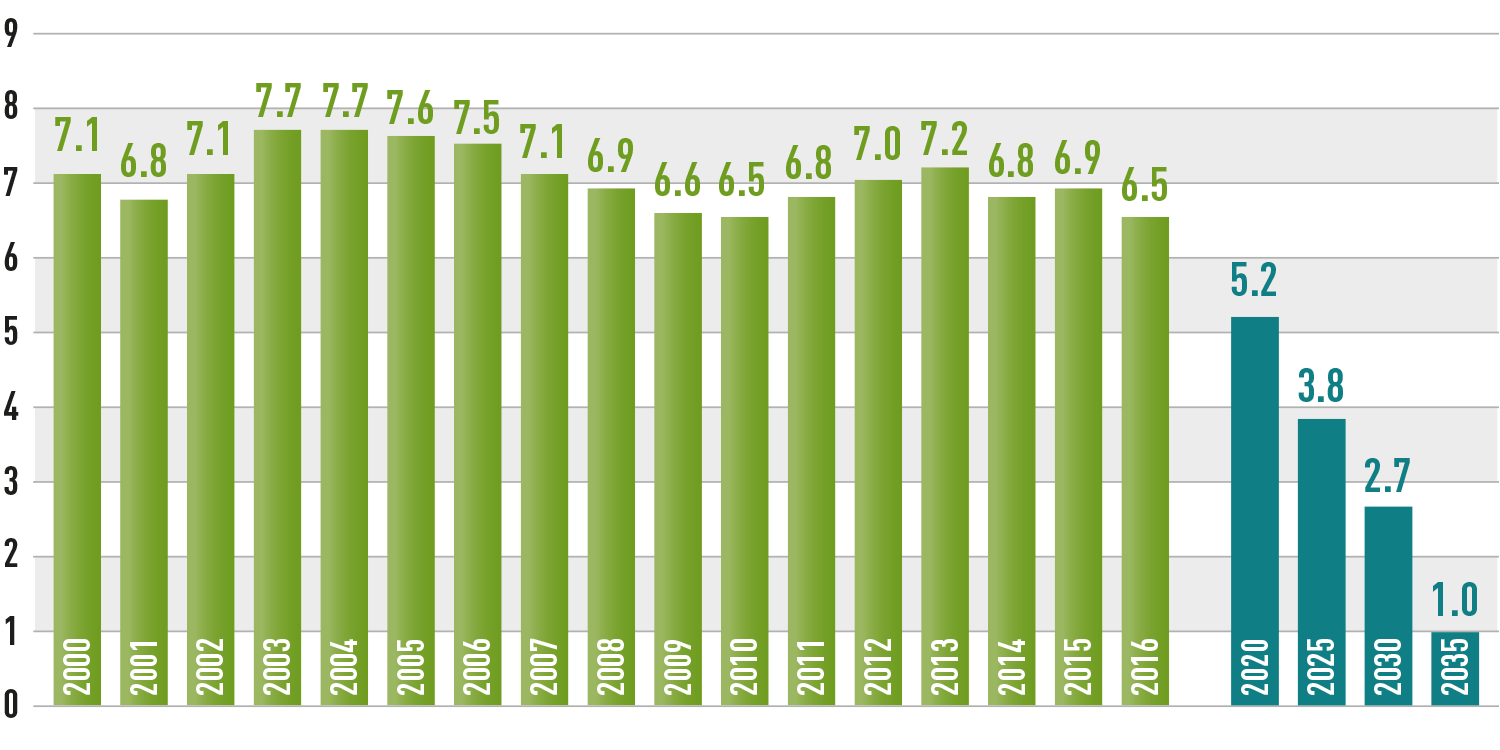

The volumes of FGD gypsum will fall considerably over the coming years as the country’s coal-fired power stations are gradually shut down. And Germany will have stopped producing FGD gypsum altogether by 2038 at the latest when the last coal-fired power station is taken off the grid. Compared to 2020, there will then be around 5.2 million tonnes less gypsum available on the market.

Germany will have stopped producing FGD gypsum altogether by 2038 at the latest when the last coal-fired power station is taken off the grid. Compared to 2020, there will then be around 5.2 million tonnes less gypsum available on the market.

The staff at CASEA and REMONDIS are being creative in their attempts to stave off the looming raw materials crisis and to increase the volumes being recycled. “We produce plaster moulds, for example, that can be used to make roof tiles,” Ketteler said. “These moulds last for a while but at some time or other their useful life is over. Both REMONDIS Central Rhine and we take these old moulds back and use the recycled gypsum to make new products.”

In a different project, the company has set up a separate collection scheme for used dental plaster from dental practices. Dental plaster is used by dentists to make, for example, imprints of their patients’ teeth. “And they use quite a bit of material,” Ketteler commented. And yet the amounts generated are too small for most recycling businesses. With this in mind, CASEA joined forces with ERNST HINRICHS Dental GmbH and SILADENT Dr. Böhme und Schöps GmbH to launch a project to recover this sought-after raw material. “The dental practices and dental labs store their used plaster in the same box that they get their new dental plaster in and then send it back to HINRICHS,” Ketteler explained. The plaster would probably end up in the residual waste bin if they did not have access to this take-back scheme.

Volumes of FGD gypsum to 2016; from 2020: calculations according to the recommendations of the WSB Commission [‘Growth, Structural Change & Employment commission’]

Source: Schwarzkopp, Fritz; Drescher, Jochen; et al.: The demand for virgin and secondary raw materials from the rock and earth industry in Germany until 2035, published by the bbs (Federal Association of Building Materials), available online in German at: https://www.baustoffindustrie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/bbs/Dateien/Downloadarchiv/Rohstoffe/Rohstoffstudie_2019.pdf (14.01.2024)

The gypsum circular economy is more than just recycling

All these projects, however, will hardly be enough to close the gap created by the loss of the FGD gypsum from the 2030s onwards. Which is why CASEA will continue to extract natural gypsum from its quarries in Ellrich (German state of Thuringia), Dorste (Lower Saxony) and Sulzheim (Bavaria). The company also acquired a gypsum producer based in the Spanish town of Navarra back in 2020. “Spain has the largest reserves of natural gypsum in Europe,” Ketteler continued. This takeover not only strengthens the company’s independence but will also help to secure supplies of the raw materials for the German building materials industry once the coal-fired power stations are shut down.

Looking at the great discrepancy between the demand for the raw material on the one hand and the volumes of waste material generated on the other, the circular economy is more than just recycling when it comes to gypsum. “It’s all about ensuring that natural gypsum is quarried in a way that has as little impact on the environment as possible,” Ketteler explained. “Which is why we already start restoring the landscape while we’re quarrying the gypsum and even beforehand to compensate for our activities. That way we enhance the landscape and preserve biodiversity.” The long-term goal must be, however, to increase the amount of gypsum-based waste being recycled for reuse. Only if gypsum-based waste is collected separately and recycled can this excellent building material display its greatest strength: its circularity. Water out, water in.

“It’s all about ensuring that natural gypsum is quarried in a way that has as little impact on the environment as possible.”

Carsten Ketteler, Managing Director of CASEA

Image credits: © REMONDIS