One of the biggest hurdles to social and economic development in India is water supply. With over 1.25 billion inhabitants, India has the second-largest population in the world behind China. This subcontinent is home to around 18% of the world’s population but has just over 4% of global water resources. According to studies published by the United Nation’s Environment Programme (UNEP), India could already find itself suffering from extreme water stress in 2025.

In 2022, India experienced its hottest summer ever with temperatures reaching up to 47°C.

The reasons behind India’s water shortage:

On average, 37% more groundwater is withdrawn in India than can be naturally renewed.

The water available from surface waters is becoming scarce.

Many rivers and lakes are becoming increasingly polluted.

The falling water table in the north west and south east of the country has led to the groundwater reserves in 20 cities (including Delhi, Chennai and Bengaluru) being almost completely used up.

The water pipe networks are in such a bad state that up to 40% of the water being transported is lost.

There are few incentives to use water sparingly due to the heavily subsidised prices for farmers and households.

The demand for drinking water is stead-ily increasing; not only because the population is growing but also because industrial businesses need more water.

Frequent extreme weather events: in 2022, the country experienced its hottest summer ever with temperatures reaching up to 47°C.

So where is India’s fresh water?

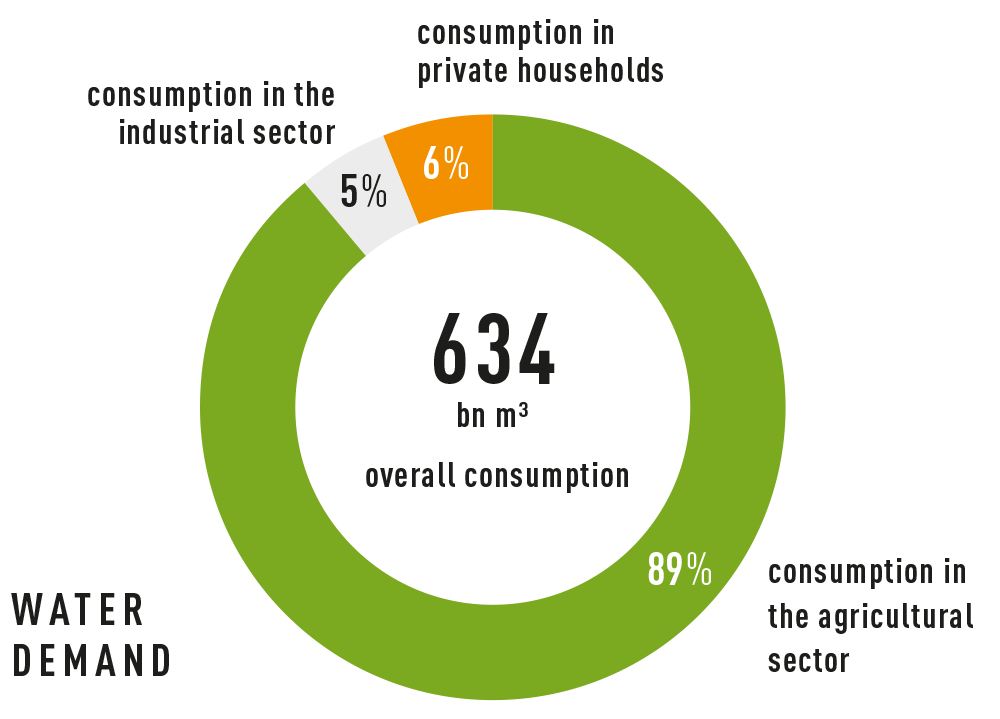

India consumes around 634 billion cubic metres of water every year. A whole 89% of fresh water supplies are used by the agricultural sector. Private households consume a mere 6% of the water and the industrial sector’s share is very low lying at 5%. Approx. 40% of households have tap water connections; in rural areas this figure drops to just 20%. Experts are forecasting that the demand for water from public sector institutions and private households will have doubled by 2030. What’s more, they expect the demand for water from the industrial sector to quadruple.

Wastewater treatment is rare

The situation is no better with the wastewater: 62 billion litres of wastewater are generated in the country’s towns and cities every day and just one-third of this is treated. Across the whole of India, there are 615 operational sewage treatment plants with a capacity to treat 24 billion litres. For the most part, the plants only have mechanical treatment systems. The quality of the drinking water also suffers because wastewater is discharged into the ground, rivers and lakes. Mumbai is the only city that fulfils all the statutory requirements. According to an investigation carried out by the Bureau of Indian Standards, other large cities, such as Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai, were not able to meet up to ten of the eleven criteria.

“Modern wastewater management, including ZLD, will play a decisive role in overcoming the water crisis that so many regions around the world are facing.”

Dr Keno Strömer, Managing Director of REMONDIS Aqua India

Pankaj Kumar, REMONDIS Aqua India, is the technical head of EVONIK’s ZLD facility

Recycling is growing in importance

With their supplies of drinking water dwindling, Indian councils are turning more and more to wastewater recycling. The country’s capital city, New Delhi, has 36 plants that generate 1.6 million cubic metres of process water every day. Mumbai intends to have built processing facilities with a daily capacity of 1.8 million cubic metres by 2025. And one particular system is becoming increasingly important for industry: zero liquid discharge, which, as the name suggests, creates a wastewater-free production cycle.

Many German companies have, therefore, made their way to India with their technologies and product solutions to support the country in its efforts to improve its water supply and wastewater treatment systems. For many years now, Dr Keno Strömer, managing director of REMONDIS Aqua India, has been looking into India’s vanishing water supplies – also from a scientific point of view. He is convinced that “modern wastewater management, including ZLD, will play a decisive role in overcoming the water crisis that so many regions around the world are facing.”

A partnership reducing water loss

Which is why, working closely with REMONDIS Aqua, EVONIK also recently opened its first plant in Dombivli, India, that uses zero liquid discharge (ZLD). The ZLD facility cleans and recycles the wastewater at the end of an industrial process so that there is very little or no wastewater left over. This not only enables water to be used more efficiently, it also significantly reduces the plant’s volumes of waste liquid.

Evonik has been developing location-specific action plans as part of its global water management strategy. It has, in particular, been focusing on its plants that are located in regions that may be affected by a water shortage.

Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD)

ZLD is system for treating wastewater that is particularly suitable for large industrial businesses. By using ZLD, water is kept in a continuous loop so that it can be treated and reused again and again. The result is a production system that generates absolutely no wastewater. Thanks to ZLD, costs are cut, water reserves conserved and the environment protected.

How REMONDIS Aqua supports India

Being an expert in wastewater treatment and water supply, REMONDIS Aqua realised early on that there was a need for ZLD in India. It has already launched a comprehensive range of services related to this system over the last three years – and this despite the fact that ZLD technology is extremely complex both to design and run. REMONDIS Aqua is one of just a handful of companies with the necessary expertise and many Indian businesses and international firms based in India have already benefited from its knowledge. Besides helping to secure the future of industrial firms in India, the system also has a positive impact on the environment, helping to stabilise the whole of the Indian water supply network.

Image credits: image 1: Adobe Stock: Sahil Ghosh; image 2: REMONDIS