With the electricity grid having no buffer, electricity supply is a sensitive matter. If millions of people turn the lights on in their homes and sit in front of their TVs, then the grid operator must simultaneously add more electricity to the network to ensure the system remains balanced. If they fail to do this then the voltage in the grid will fall below the critical point. And then it is there, the dreaded blackout.

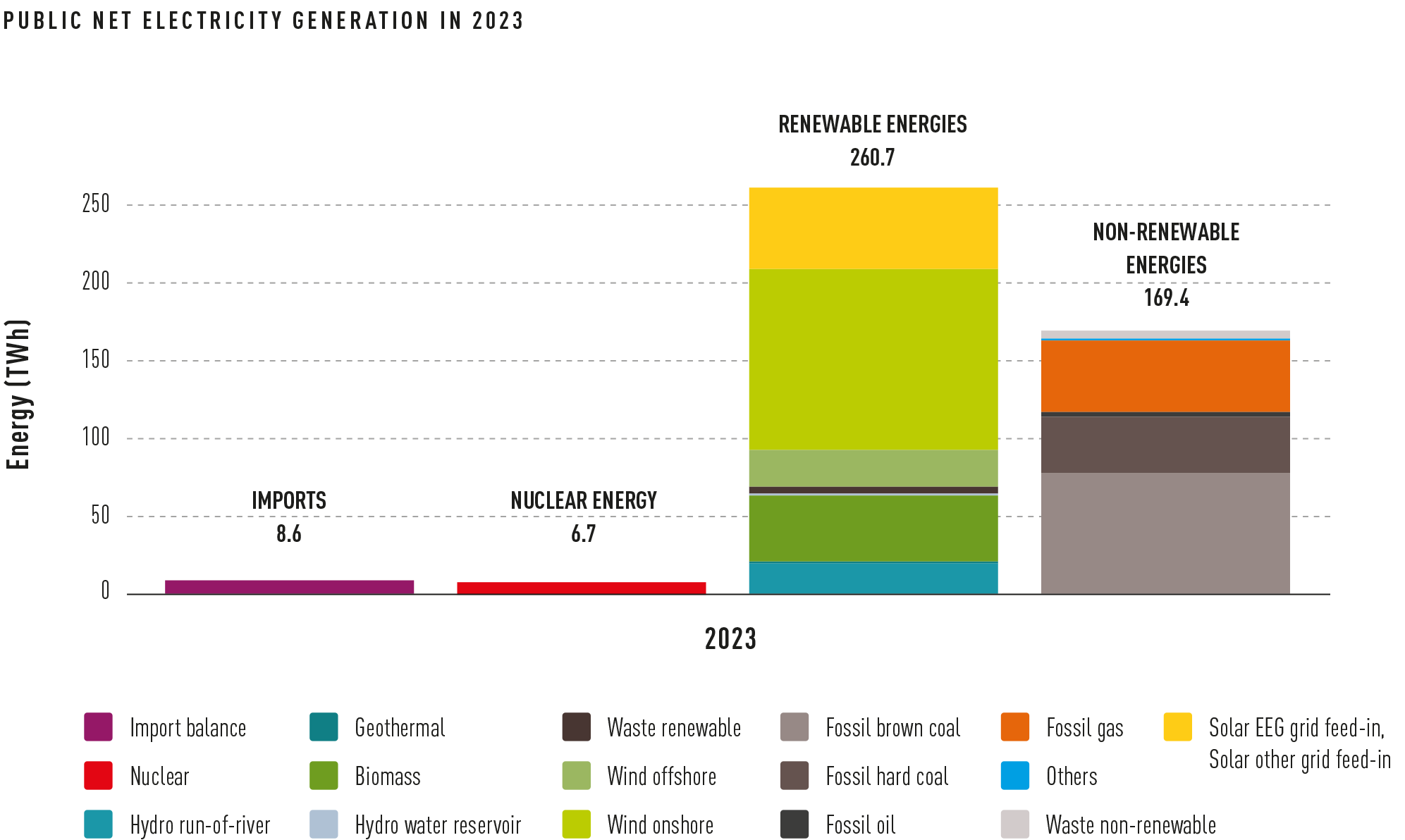

Keeping the system balanced was no great challenge when Germany’s electricity was generated by large fossil-fuel-fired power stations and nuclear power plants, especially as the behaviour of industry and consumers was predictable as they did not generate their own electricity back then. Things were different in Germany, though, in 2023 when almost 60% of the electricity generated came from renewable sources. Decentralised energy production and a dependency on the weather are what is shaping this new world. And, on top of this, society is facing a new wave of electrification and new key consumers, caused for example by the transition to e-mobility.

Creating a buffer

Converting electricity generation systems to counteract the climate crisis is creating some novel challenges for the electricity grid. Instead of having a clear and manageable number of power stations, there are now countless wind turbines and solar systems dotted around the country. This development is proving to be so dynamic that the Bundesnetzagentur, the authority in charge of Germany’s key infrastructure, has limited itself to publishing the amount of electricity that can be generated rather than the number of systems that have been installed.

And as if that wasn’t a big enough challenge for the grid, there is a new trend: customers are installing their own systems and generating their own electricity. Be it solar panels on the roof – and not only on REMONDIS’ buildings – or balcony solar generators in people’s homes. Being able to plan costs and be energy-independent are the two main arguments fuelling this trend.

Operators of wind and solar farms are also looking for ways to get a better price for their electricity. The prices at the EEX electricity exchange in Leipzig drop almost immediately when the wind blows and the sun shines; in some cases there are even negative prices. In 2023, that was the case on 46 days for at least one trading period. In other words, the electricity producers have to pay to hand over their electricity.

All this means that storage solutions are key for all of the stakeholders involved in this business. If a buffer is created then it is easier to balance out demand and supply and it reduces the need for grid operators to intervene, helping to keep costs lower. It is true that pumped storage power plants are one well-established way to solve this problem. Both their size, however, and the topography required mean that it is not possible to build them everywhere.

New technologies, such as power-to-gas (P2G), will also be used in the future. This process sees the generated electricity being used to produce a fuel gas such as hydrogen or methane – ideally on site where the electricity is generated – that can then be stored. There are very few plants actually doing this at the moment even though the technology is already available. Nowadays, experts describe the efficiency of this generation system as being ‘reasonable’ at over 50%. Despite this, though, such technology is likely to be something for the future. Everything is pointing towards batteries as being the short-term option.

E-mobility

The versatile battery, however, is not only playing a key role in the energy transition but in the transport transition as well. Ever since the EU set the course for the internal combustion engine to be replaced by e-mobility, the number of new EVs on the road has been rising at a very rapid rate – even if the number of electric cars is still comparatively low and makes up around 4% of all cars in Germany.

Ramping up the production of EV batteries is the main challenge being faced by the automobile industry all around the world as it looks to restructure its business. And things are unlikely to change any time soon. This development also underlines the EU’s intention to move towards e-mobility having set out in law that combustion engines must be phased out from 2035 onwards. Looking at the importance of the automobile industry for Germany’s economy, politicians must take steps to ensure that this key expertise and these jobs remain in the country. This is the reason why new projects are given so much attention in the media, such as the recently approved Northvolt factory that is to be built on the west coast of Schleswig-Holstein.

Wireless homes – where all technology is connected

Another area that has seen an increase in demand for batteries is the so-called smart home. Electrifying people’s homes requires a large number of different-sized, single-use and rechargeable batteries for sensors, remotes, cameras and motion detectors. At the end of the day, we do not want to have to plug all these aids into our wall sockets or use chargers all the time. Autonomous household devices, such as robot vacuums and automatic door openers, also need rechargeable batteries. And the smartphone – the device with the app to control this new world – obviously needs a rechargeable battery as well.

Renewables supplied 59.7% of public net electricity production in 2023. Imports and nuclear energy played only a minor role (source: Fraunhofer ISE/energy-charts.info)

A geopolitical challenge

One thing is very clear: the demand for batteries will continue to grow rapidly. In a recent study, RWTH Aachen University and the management consultants Roland Berger predicted that the demand for batteries will increase 18-fold between 2020 and 2030. In this study, they state that the demand will grow by an average 34% year on year during this period. This growth is primarily being sustained by lithium-ion batteries. Increasingly though, sodium-ion batteries are also playing a role even if their lower energy density and their greater weight limit their potential areas of use. Unlike lithium, which is mined in just a few countries such as Argentina, Australia, Chile and China, there are much larger volumes of sodium available in the four corners of our world.

The scarcity of lithium is and will continue to be, therefore, a growing challenge, especially as it is essential for other sectors such as the glass and ceramics industry. With China being the main driver pushing up the price for lithium, 2023 saw a backward change in this trend. However, once China’s economy picks up again, the price for lithium is likely to rise. Looking at the current geopolitical situation, this means that lithium may possibly be one of the raw materials that will become scarce for political reasons.

Recycling

And so it is no surprise that the scarcity of the raw materials and the geopolitical risks mean that recycling activities in this area – primarily lithium-ion batteries – are rapidly increasing and that a whole range of stakeholders, including those beyond the traditional circular economy players, are driving forward ideas so that they get a piece of this future pie, for example for their own battery production operations.

You can find more articles on batteries here:

Image credits: image 1: Shutterstock: Artiste2d3d, Shutterstock: FreshPaint, Shutterstock: Hakan GERMAN, Shutterstock: Ljupco Smokovski, Shutterstock: kunta surirug, Shutterstock: xpixel, Shutterstock: Wirestock Creators; image 2: Shutterstock: xpixel, Shutterstock: Wirestock Creators