Instead of driving diesel or petrol cars and heating up the climate, people should now be using carbon-free EVs charged with green electricity – preferably from the solar panels on their own roofs. Green cars for a green conscience.

Reality tends, however, to be more complicated than the narrative. If the lithium-ion batteries in the EVs are not recycled, then it is practically impossible for e-mobility to live up to its promise of being sustainable. The Bavarian car manufacturer BMW calculated that the carbon footprint of a newly registered EV is around 40% bigger than that of a comparable model with an internal combustion engine. This can primarily be put down to the carbon-intensive mining of the raw materials required to make the EV’s lithium-ion battery: e.g. lithium, nickel and cobalt.

If the lithium-ion batteries in the EVs are not recycled, then it is practically impossible for e-mobility to live up to its promise of being sustainable.

Christian Kürpick knows all about lithium-ion batteries. He is a project manager at REMONDIS’ subsidiary RETRON. RETRON primarily focuses on so-called industrial lithium-ion batteries – i.e. on batteries that are found, for example, in electric cars, bikes and scooters.

RETRON’s bread and butter is selling and renting out boxes that allow used lithium-ion batteries to be safely stored and transported. “Bike retailers are, for example, obliged to take back used e-bike batteries,” Kürpick said. RETRON’s boxes ensure that the faulty batteries do not catch fire and burn the bike shop down.

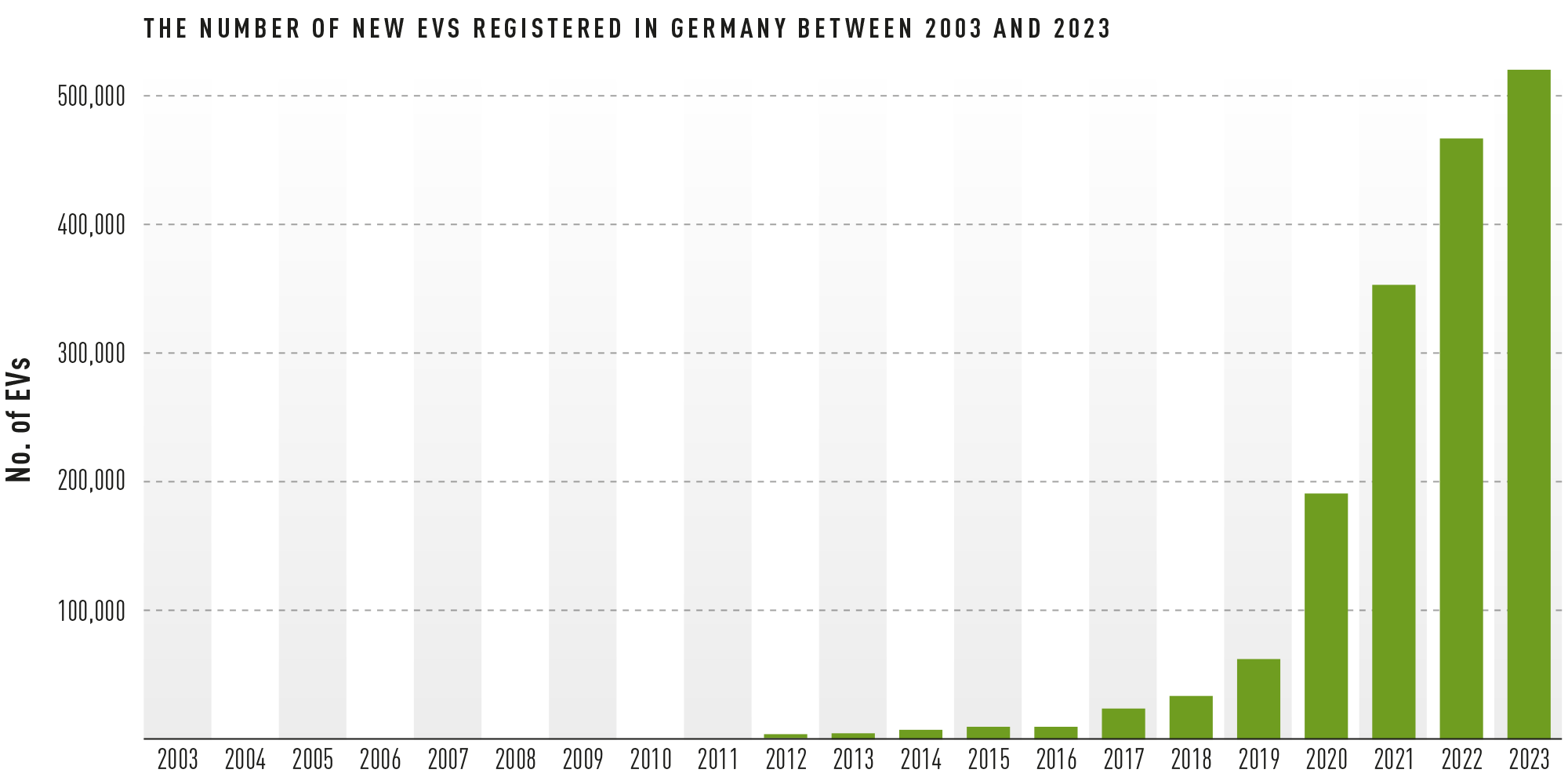

Source: KBA, © Statista 2024

There are currently around 2.9 million EVs on Germany’s roads.

First dismantle, then recycle

For a while now though, Kürpick and his colleagues have also been looking into the recycling of lithium-ion batteries – and this is anything but simple. The batteries are first pre-treated before they are actually recycled, i.e. they are first dismantled and taken apart as far as is possible. “Some batteries are up to 2.7 metres long and weigh up to 1,500 kilos. These have to be taken apart,” Kürpick continued. The so-called ‘good parts’ are then separated from the dismantled materials. These are the components that do not need to be recycled and can be used straight away to produce new batteries. “This is a form of reuse and absolutely in keeping with the circular economy.” The other parts – mostly plastics and metals – are sent to other REMONDIS Group companies or other metal processing businesses for recycling.

Unfortunately, recyclers often find themselves facing problems as soon as they start to dismantle the lithium-ion batteries. Rather than thinking about how their batteries can be recycled, some manufacturers optimise their products so that they get the greatest possible range from the battery. “Some producers, for example, cover the cells in their battery pack with foam.

This allows the heat in the battery packs to be dissipated more efficiently. But then it’s simply not possible to get to the parts that could theoretically be reused.” According to Kürpick, these are commonly referred to as ‘asshole batteries’ or ‘ultra-asshole batteries’ by industry experts in Germany.

Cold and warm recycling

Once they have been pre-treated, the batteries can then be recycled. “We differentiate between ‘cold’ and ‘warm’ recycling,” Kürpick explained. Both recycling methods have their advantages and disadvantages. When the cold recycling system is deployed, the battery must first be completed depleted – well below the so-called deep discharge point. “This can last for up to three to four hours,” the RETRON expert continued. Not until this stage has been completed can the battery be safely shredded. The shredding process creates a mass of very different materials that is sometimes referred to as a ‘black mass’ because of its colour. This black mass is separated into its individual fractions using a wet chemical process, known as hydro-metallurgy. Once this has been done, materials such as cobalt, nickel, manganese and lithium can be supplied to battery manufacturers.

The warm recycling system sees the battery being heated up to around 500°C to 600°C straight away without having gone through a deep discharge beforehand. There is no need for the deep discharge stage as the thermal process allows any remaining energy in the battery to escape. This thermal recycling method also creates a black mass. “The quality of the black mass produced by the thermal treatment is lower than that produced by cold recycling. The biggest advantage here, though, is that the battery doesn’t need to be discharged first. This means that recycling facilities can have a much bigger throughput than the plants that only use the cold recycling system.”

Businesses planning a lithium-ion battery recycling plant need to know now how the market is likely to develop over the coming years.

Still not enough batteries to recycle

Recycling lithium-ion batteries is not a mass market activity yet. According to Kürpick, there are currently around 2.9 million EVs on Germany’s roads. Figures published by the KBA [Federal Motor Transport Authority] show that a total of 1.7 million new EVs were registered between 2003 and 2023 – although the numbers before 2011 are more cosmetic. The real EV boom began just three years ago. 524,000 new EVs were registered in 2023 – this figure was just over 63,000 in 2019.

“An EV has a service life of approximately eight to ten years,” said Kürpick. “Which means we still need to wait a few years until a significant volume of lithium-ion batteries from the transport sector reaches the recycling market. This is the reason why there aren’t any recycling plants operating on an industrial scale yet. Many of the facilities currently recycling such batteries are pilot plants.”

The situation is made more difficult by the dynamics of the battery market as they increase the risk of recyclers backing the wrong horse. “LFP batteries, for example, were standard just a few years ago. Then the NMC batteries came along. Today, the trend is tipping back in favour of LFP batteries. This all makes it really difficult to plan ahead,” Kürpick explained. The backdrop to all this is that the value of the black mass differs greatly depending on whether the market wants LFP or NMC batteries. “While it’s the nickel and cobalt that are the valuable metals in the black mass when it comes to NMC batteries, it’s just the iron and phosphorus for LFP batteries. That makes them two quite different business cases.”

Recycling capacities must increase considerably over the coming years

Businesses planning a lithium-ion battery recycling plant need to know now how the market is likely to develop over the coming years. “Which is why we and the large car manufacturers are all keeping a very close eye on the developments,” Kürpick continued.

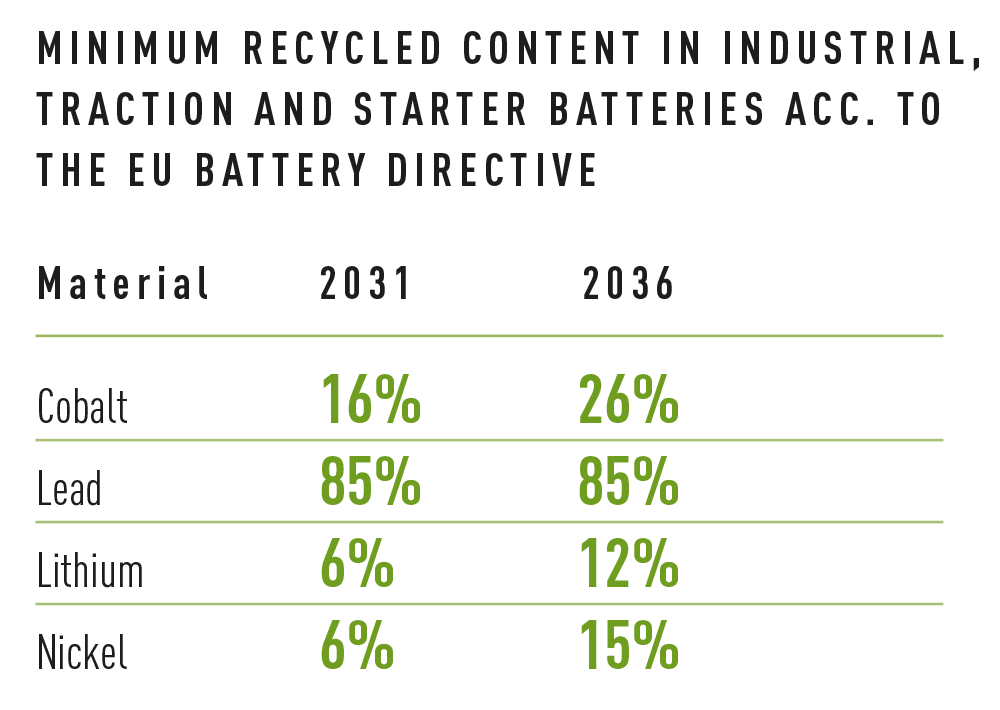

One thing is very clear: the recycling capacities must be considerably increased over the next few years. The EU’s new Battery Directive stipulates that battery manufacturers must use a certain amount of recyclate in their new industrial, traction and starter batteries. The new directive came into force last August but the minimum recycled content requirements do not apply until 2031 and 2036 respectively. This corresponds to the expected return of EVs in a few years’ time.

Six percent recycled lithium really is not a huge amount. But it is a start and this figure will gradually rise. So that electric vehicles truly can become green cars.

You can find more articles on batteries here:

Image credits: image 1: Adobe Stock: Lena Balk, Adobe Stock: Veniamin Kraskov, Shutterstock: majeczka, Shutterstock: Chesky, Shutterstock: patruflo, Shutterstock: by-studio; image 2: Adobe Stock: womue, Shutterstock: IM Imagery; image 3: Adobe Stock: Venka